Beeshroomed: The Symbiosis That Shaped Civilization

The first bee shaman lived 5,300 years ago in what would later be called the Alps. We know this because when his mummified body was discovered in 1991, preserved in ice and later named Ötzi, researchers found something extraordinary in his medicine pouch: traces of Fomes fomentarius, the tinder fungus, and bee propolis mixed together in a small leather sack.

The Ancient Alliance

The story of humanity’s relationship with bees and fungi stretches back far beyond Ötzi, to the very dawn of our species. Cave paintings in Spain dating to 8000 BCE show honey hunters scaling cliff faces with handmade rope ladders, braving angry swarms to collect precious honey combs. What the paintings don’t show is what these early humans already understood: that the relationship between pollinator and plant was fundamental to their survival.

Meanwhile, in forest floors across the ancient world, vast networks of mycelia were silently spreading beneath the soil, connecting trees in what scientists now call the “Wood Wide Web.” These fungal networks allowed trees to share resources and information, creating resilient forest ecosystems that our ancestors relied upon.

Archaeological evidence suggests that by the Neolithic period, humans had begun to intentionally cultivate both mushrooms and honey bees. The earliest evidence of beekeeping comes from pottery vessels discovered in Northern Africa dating to around 9,000 years ago. Clay hives with distinctive entrance holes show how early agriculturalists had already developed sophisticated understanding of bee behavior.

The Knowledge Keepers

In ancient Egypt, bees held special significance. The bee was a royal symbol, adorning the pharaoh’s cartouche. Honey was considered the food of the gods, and apiaries were maintained by specialized priests. Egyptian medical papyri dating to 1550 BCE describe over 900 medicinal formulas, many containing honey for its antimicrobial properties.

What’s less known is that many of these same medical texts also contained prescriptions using various fungi. The Ebers Papyrus specifically mentions “the growth that appears on trees after rain” as treatment for inflammation and wounds.

In ancient China, the earliest text on medicinal substances, the Shennong Ben Cao Jing (compiled around 200 CE), classified fungi like reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) among the highest tier of medicinal substances. These were believed to promote longevity and spiritual well-being. The same text described honey as “sweet in taste, calm in nature,” and prescribed it for detoxification and balancing internal energies.

The Forgotten Knowledge

Indigenous cultures worldwide maintained intricate understanding of both bees and fungi. The Maya cultivated stingless bees (Melipona beecheii) for over 3,000 years in specialized log hives called “jobones.” They understood that these bees were essential pollinators for their crops and that the ceremonial honey produced was both medicine and sacred offering.

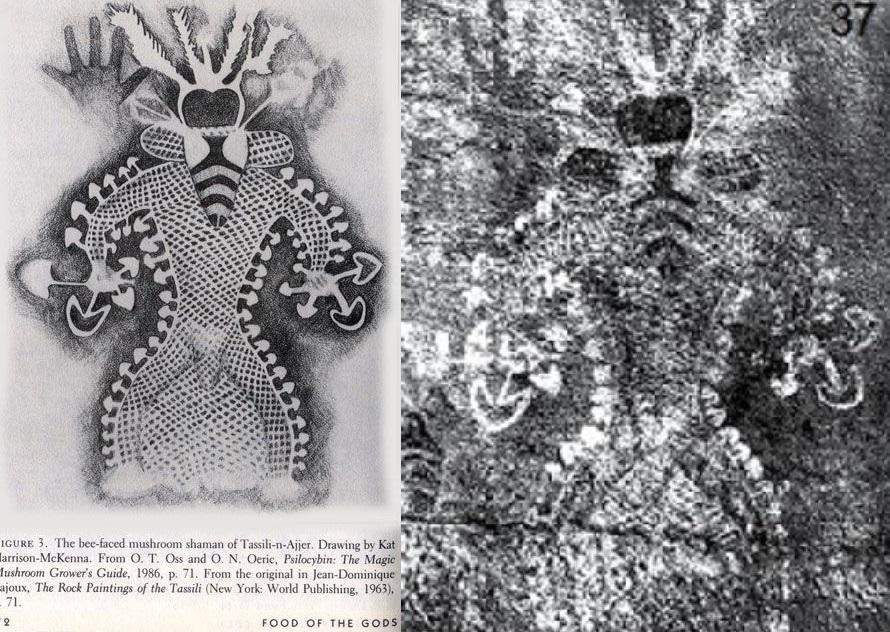

Mycolatry—the worship of mushrooms—appears in multiple ancient cultures. Mushroom stones dating from 1000 BCE to 900 CE found throughout Guatemala, Mexico, and El Salvador suggest ritualistic use of psychoactive mushrooms. These ceremonies weren’t mere recreation; they were sophisticated technologies for ecological management and cultural transmission.

The knowledge systems that maintained balance between humans, bees, and fungi began to fracture with the onset of industrialization. The introduction of refined sugar reduced the cultural importance of honey. The scientific revolution, while advancing knowledge in many areas, dismissed much traditional ecological understanding as superstition.

The Modern Rediscovery

It wasn’t until the late 20th century that science began to catch up with ancient wisdom. Mycologist Paul Stamets pioneered research showing how fungi could remediate toxic waste, provide sustainable alternatives to conventional pesticides, and potentially treat various human diseases. His 2008 TED talk, “6 Ways Mushrooms Can Save the World,” introduced millions to the forgotten importance of fungal ecology.

Simultaneously, the global decline of bee populations awakened humanity to the essential role these insects play in food security. Research by Dr. Marla Spivak at the University of Minnesota demonstrated that propolis—the resinous mixture bees collect from tree buds and sap—helps maintain bee immune systems and hive health, confirming what Ötzi might have known millennia ago.

The most remarkable discovery came in 2019 when researchers at Washington State University found that certain fungi in the genus Metarhizium protect bees against the deadly varroa mite without harming the bees themselves. This symbiotic relationship between fungi and bees had existed all along, waiting to be rediscovered.

The Future Symbiosis

Today, as we face unprecedented ecological challenges, the ancient relationship between humans, bees, and fungi offers vital lessons. Urban beekeeping has surged worldwide, with cities like Paris, London, and New York hosting thousands of hives on rooftops and in community gardens. Citizen scientists document bee behavior and population patterns through initiatives like the Great Sunflower Project.

Mycoremediation projects utilize fungi to clean up oil spills, industrial contamination, and agricultural runoff. Companies are developing packaging materials from mycelium as sustainable alternatives to plastics. Researchers explore using fungal compounds to treat conditions ranging from depression to cluster headaches.

Perhaps most promising is the emerging field of regenerative agriculture, which integrates principles from permaculture, indigenous knowledge systems, and modern science. These methods emphasize soil health through fungal networks while creating habitat for pollinators.

The story of bees, mushrooms, and humanity continues to unfold. As Ötzi knew all those millennia ago, these relationships aren’t merely useful—they’re essential to our survival and prosperity. In rediscovering these ancient symbioses, we may find solutions to our most pressing modern problems.

As the Kayapó people of the Amazon say: “The forest makes the bee, the bee makes the forest, and both make us.”

Leave a comment