Throughout human evolution, our relationship with plants has shaped not only our physical survival but our consciousness itself. What ancient cultures often called “the food of the gods” – those plants with remarkable properties to alter perception and cognition – represents one of humanity’s most profound discoveries. Our earliest ancestors developed intimate knowledge of plants through necessity and careful observation, gradually identifying those with properties beyond mere sustenance.

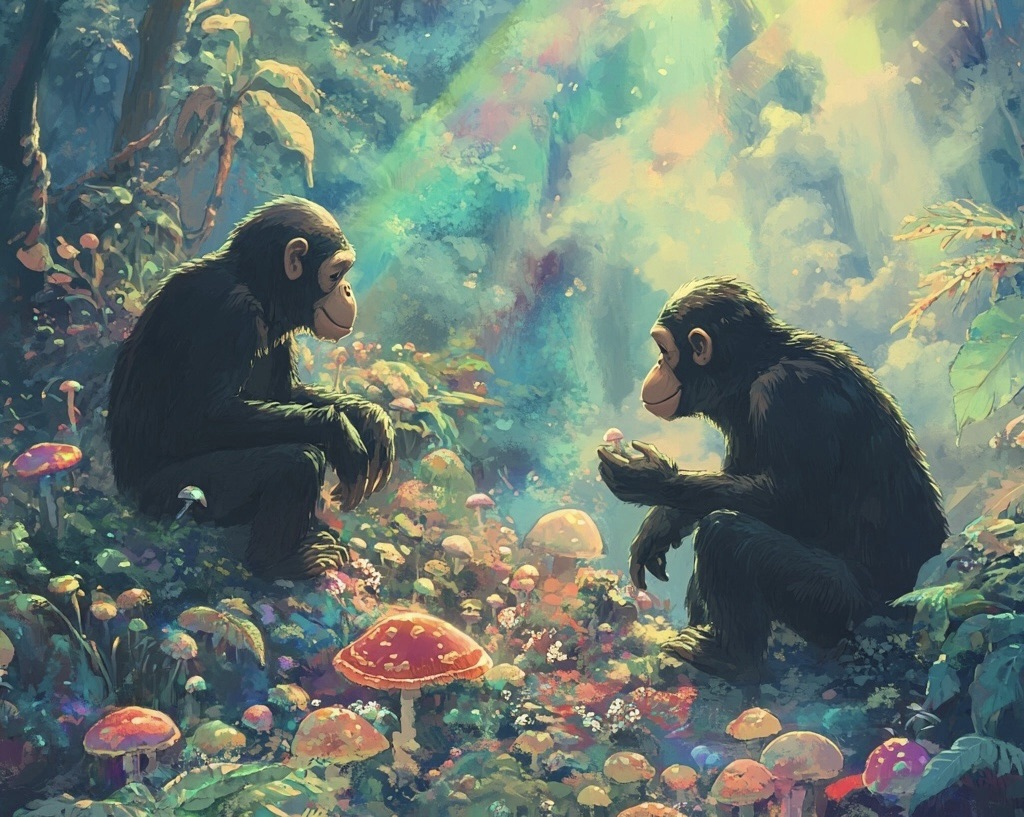

The evolutionary history of these relationships spans millennia, with evidence suggesting early humans recognized and utilized plants with psychoactive properties over 10,000 years ago. Cave paintings and archaeological findings indicate ritualistic use of plants across diverse regions, from psilocybin mushrooms in Europe to ayahuasca in the Amazon. This suggests not isolated incidents but a fundamental aspect of human cognitive development, as we sought to understand the natural world and our place within it.

Throughout history, various psychological paradigms have framed our understanding of these plants. Ancient animistic worldviews saw them as embodiments of spirits or deities, while classical civilizations from Greece to China incorporated them into sophisticated philosophical and medical systems. The medieval period often recast these relationships through religious frameworks, sometimes preserving plant knowledge, sometimes condemning it. The modern scientific paradigm initially dismissed traditional plant wisdom as primitive superstition before gradually recognizing the complex pharmacology underlying ancestral practices.

Different cultures worldwide developed specific relationships with plant teachers. In the Americas, various indigenous nations established elaborate ceremonies around plants like peyote and tobacco. Asian traditions integrated cannabis and ephedra into religious and healing systems. African cultures developed rituals around iboga and other botanical allies. These weren’t merely cultural curiosities but sophisticated knowledge systems refined over generations of careful empirical observation.

The concept of entheogens – substances that “generate the divine within” – emerged to describe plants used specifically for spiritual purposes. Unlike modern recreational drug use, traditional entheogenic practices were carefully bounded by ritual, community oversight, proper intention, and extensive preparation. The sacred context of these encounters was inseparable from the experience itself, with plants regarded as teachers rather than commodities.

Our ancestors understood the blessings of this knowledge came with responsibility. Many indigenous traditions speak of the “seven generations” principle – the idea that decisions should consider impacts seven generations into the future. This ethical framework guided the transmission of plant wisdom, ensuring knowledge was passed down with appropriate reverence and caution. Today, we face the challenge of honoring these traditions while addressing contemporary needs.

Bringing this knowledge forward requires careful integration rather than appropriation. Modern scientific research on plants like psilocybin, cannabis, and ayahuasca validates many traditional claims while offering new understanding of their mechanisms. This rediscovery presents an opportunity to bridge indigenous wisdom with contemporary approaches to mental health, ecological awareness, and spiritual well-being – provided we proceed with respect and appropriate attribution.

Various schools of wisdom – from indigenous knowledge systems to Eastern contemplative traditions to Western psychology – offer complementary perspectives that, when thoughtfully integrated, create a more complete understanding. This integration isn’t about reducing sacred plants to clinical tools or recreational substances, but recognizing their potential contribution to addressing modern challenges like widespread mental health issues, ecological disconnection, and spiritual alienation.

The visionary harmony of biology and technology offers new possibilities. Advanced neuroimaging can now visualize what shamans have described for centuries. Sustainable cultivation techniques can reduce pressure on wild plant populations. Digital technologies can help preserve and share traditional knowledge with appropriate cultural protections. The intersection of ancient wisdom and modern capabilities presents unprecedented opportunities for human growth and planetary healing.

In its essence, the story of “food of the gods” reminds us of our fundamental connection to the plant world – not as masters but as partners in an ongoing dialogue spanning countless generations. By approaching this knowledge with humility, respect for its origins, and careful discernment, we honor both those who preserved it through difficult times and those who will inherit it in an uncertain future.

Testament to The Use of Plants in Human Culture

Terence McKenna’s “Food of the Gods” presents a provocative theory about human evolution and consciousness, suggesting that our ancestors’ consumption of psychoactive plants—particularly psilocybin mushrooms—played a crucial role in our cognitive development. Published in 1992, McKenna’s work emerged during a time when Western culture was reconsidering its relationship with psychedelics following the counterculture movement of the 1960s and subsequent prohibition. His “stoned ape theory” proposes that early hominids in Africa encountered psilocybin mushrooms growing in cattle dung as they transitioned from forest to savanna environments, and that these compounds enhanced visual acuity, arousal, and linguistic capabilities—accelerating the development of culture and consciousness.

The historical context of McKenna’s work is significant. He wrote during a period when mainstream science was largely dismissive of psychedelics, yet anthropological evidence had been accumulating about the widespread use of mind-altering substances across human societies. McKenna challenged the dominant evolutionary narratives that emphasized tool use and meat consumption, instead highlighting the neurological impacts of plant compounds on human consciousness. His ideas resonated with the growing environmental and New Age movements of the late 20th century, which were questioning industrial society’s disconnection from nature.

Human evolutionary history, as McKenna interpreted it, was profoundly shaped by our relationship with plants. While conventional anthropology focused on physical adaptations and social structures, McKenna emphasized the “symbiotic” relationship between humans and psychoactive plants—what he termed the “vegetable mind.” He suggested that the rapid tripling of the human brain size over a relatively short evolutionary period might be connected to dietary changes that included psychoactive substances, which stimulated neurogenesis and novel cognitive functions. These plant teachers, he argued, helped forge the symbolic thinking and introspective capabilities that distinguish human consciousness.

The dominant psychological paradigms during McKenna’s time were primarily materialistic, viewing consciousness as an epiphenomenon of brain activity. Behaviorism had given way to cognitive psychology, but mainstream science still largely ignored altered states of consciousness as worthy of serious study. Historically, Western psychology since the Enlightenment had emphasized rationality and dismissed visionary or mystical experiences as delusions or pathologies. McKenna’s work challenged these paradigms by suggesting that expanded states of consciousness accessed through plant medicines were not aberrations but potential gateways to evolutionary adaptation and cultural innovation.

Throughout human history, cultures have incorporated plants into their medicinal, spiritual, and social practices. From the use of ayahuasca in the Amazon, peyote among Native American tribes, iboga in Central Africa, to cannabis across Asia and the Middle East, plant medicines have been integral to human healing traditions and spiritual practices. McKenna argued that the modern West’s disconnection from these plant allies represented not progress but a profound loss—a “dominator culture” that severed our relationship with nature’s wisdom and enforced a limiting consensus reality through alcohol and consumer culture.

Entheogens, a term coined in the 1970s to describe substances that “generate the divine within,” have been central to many religious and spiritual traditions. These plant compounds—including psilocybin mushrooms, ayahuasca, peyote, and others—have been used for millennia in structured ritual contexts to facilitate healing, divination, community cohesion, and encounters with the sacred. McKenna proposed that these substances didn’t simply produce hallucinations but actually revealed deeper layers of reality ordinarily filtered out by our everyday consciousness—offering insights that helped human communities navigate ecological relationships and social challenges.

Viewed through the lens of Yuval Noah Harari’s “Sapiens,” McKenna’s theories can be seen as exploring the cognitive revolution that Harari identifies as the decisive turning point in human history. While Harari emphasizes how language and collective fictions enabled large-scale cooperation, McKenna’s work suggests that plant entheogens may have catalyzed the very cognitive leap that made symbolic thinking and shared myths possible. Both thinkers recognize that what makes humans unique is not merely our tool use or physical adaptations, but our capacity for imagination, abstract thought, and the creation of intersubjective realities.

The blessing of this topic comes from our ancestors across cultures who maintained sacred relationships with plant teachers, preserving knowledge of their proper use through generations of oral tradition and careful practice. In many indigenous worldviews, these plants are considered elder beings or teachers who chose to share their wisdom with humans. The reverence shown to these plant allies—the careful preparation, the ritual context, the integration of insights—demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of consciousness exploration that stands in stark contrast to recreational drug culture.

The concept of “Seven Generations”—an ethical principle from the Iroquois Confederacy that decisions should consider impacts seven generations into the future—resonates with McKenna’s call for humanity to reconsider its relationship with psychoactive plants. He argued that our current ecological crisis stems partly from the suppression of the plant-human dialogue that once guided our species toward sustainable relationships with nature. By reconnecting with these plant teachers in responsible ways, McKenna suggested we might recover ecological wisdom crucial for the survival of future generations.

Bringing this knowledge forward for upcoming generations requires integrating scientific understanding with indigenous wisdom traditions that have preserved entheogenic knowledge. This involves not appropriation but respectful dialogue and the recognition that Western science is beginning to validate what traditional cultures have known for millennia—that these plants can facilitate healing, ecological awareness, and meaningful connection. Research at institutions like Johns Hopkins and Imperial College London now confirms that psilocybin and other entheogens can effectively treat depression, addiction, and existential distress when used in structured therapeutic contexts.

Integrating schools of wisdom means acknowledging both the scientific evidence about these substances and the ceremonial contexts that maximize their benefits while minimizing risks. It means creating bridges between neuroscience and shamanic traditions, between psychological research and indigenous protocols. This integration recognizes that these plants are neither magical panaceas nor mere chemicals, but complex teachers that interact with human consciousness in ways that require both reverence and rigorous understanding.

McKenna envisioned a future harmonizing biology and technology, where humanity’s relationship with plant intelligence could guide our technological development toward sustainable and consciousness-expanding directions rather than domination and exploitation. He suggested that the plant-human symbiosis represented an evolutionary strategy that could help us navigate our current planetary crisis—offering visionary experiences that remind us of our embeddedness in nature and inspire technological innovations aligned with ecological wisdom rather than extraction.

In essence, “Food of the Gods” invites us to reconsider our evolutionary story and our future potential. By examining the historical role of psychoactive plants in human consciousness development, McKenna challenges us to recognize these substances not as dangerous drugs but as potential allies in our collective journey toward psychological wholeness, ecological sustainability, and expanded awareness. His work reminds us that our relationship with nature’s intelligence has shaped our past and may be crucial for navigating our future on this planet.

Leave a comment